In Tamil Nadu’s Tiruppur, Bihari migrants are the new business bosses. Who do they employ?

Many migrant workers have reinvented themselves as entrepreneur-owners of textile units in Tiruppur, the export hub of Tamil Nadu. They call it ‘Tiruppur ka jadoo’. -

Many migrant workers have reinvented themselves as entrepreneur-owners of textile units in Tiruppur, the export hub of Tamil Nadu. They call it ‘Tiruppur ka jadoo’. -

March 06, 2024 Tiruppur: Tattered clothes, broken slippers, and a small bag—these were the only things that Vijay Kumar brought with him when he came to Tiruppur in 2009 from Bihar’s Vaishali district.

Today, he has transcended the tag of a “Hindi migrant worker” and become an entrepreneur-owner of a cloth printing unit himself in the Tamil Nadu textile export hub. He isn’t the only one. Hundreds of migrant workers have become entrepreneurs over the last decade. They call it “Tiruppur ka jadoo”. This trend is particularly remarkable given the growing anxiety and discomfort among Tamils that workers from the north are taking over their jobs. Now, some of the same workers who are lampooned with labels such as “paani poori”, “bhaiyya”, and “Hindi-karans” are also generating jobs.

Some even hire Tamil workers in their thriving production units. This gradual shift upends popular notions about labour migration, the so-called North-South divide, economic mobility, and cultural assimilation.

Many of these migrant entrepreneurs have seamlessly adapted to the local culture. They speak fluent Tamil, savour filter coffee, and lounge in crisp white veshtis (dhotis). At Kumar’s textile unit, a portrait of Lord Murugan, garlanded with fresh jasmine, adorns the wall. It’s flanked by a Tamil calendar with dates annotated in blue ink. Even Kumar’s English now has a noticeable Tamil lilt.

The 30-year-old, who ended his formal education after completing class 10, calls himself a “self-made entrepreneur”. After 15 years in Tiruppur, of which seven were spent as a worker in various textile units, he now employs 10 fellow Biharis in his own cloth printing business.

For him, adapting to the new culture wasn’t the biggest hurdle. It was peer pressure from his old friends. He wanted to set down new roots in Tamil Nadu, but they saw it as a stopgap, he said.

“My North Indian friends didn’t really think much about their futures,” Kumar recounted. “They were happy to keep working as migrant labourers and even made fun of me for speaking Tamil. But I had bigger dreams.”

Tiruppur has claimed the title of a ‘Make in India’ knitwear production and export hub even before Prime Minister Narendra Modi popularised the term. It is the big entrepreneurial dream city for small town North Indians. For decades, migrants from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Odisha have flocked here to work as migrant workers of production units owned by Tamils. But now some of them are rising up in the pecking order with their own micro and small textile units. They say that Tiruppur makes their upward mobility possible. For Tamils, it is the state’s “progressive work culture and lack of home-grown labourers” that has opened doors for the migrants.

“Those who have skills and aspirations to do something big are becoming entrepreneurs and Tamil society is not blocking their dreams,” said GR Senthilvel, secretary, Tiruppur Exporters and Manufacturers Association (TEAMA).

Tiruppur’s rise as a global knitwear powerhouse mirrors the gradual emergence of its migrant business community. Over the course of five decades, it has become a major supplier for global fashion brands such as Nike, Adidas, and H&M, accounting for 54.2 per cent of India’s textile exports in 2022. Once known for cotton farming and yarn production, the town switched to knitwear hosiery manufacturing in the 1970s, with farmers becoming owners of small textile units. This change coincided with the demand for affordable clothing both domestically and internationally.

In the 1980s, the town witnessed the arrival of businesspersons from Gujarat and Rajasthan who set up their textile units. It wasn’t until the 1990s, when the migrant workers started to trickle in.

It was the decade of rapid industrial and economic growth in Tamil Nadu. Ford Motors set up its factory in 1995 outside Chennai, sending a signal to the rest of the world that Tamil Nadu was open for business. Backed by an efficient administration, political will, and focus on ease-of-doing-business, Tiruppur flourished in the brave new flat world.

“If you have skills, we will welcome you—that is our mantra. It doesn’t matter where you are from, to which caste you belong, and which religion you practice. Tamil society welcomes people who want to work,” said Senthilvel.

Migrants reportedly make up about around half of the 6 lakh workers at the town’s roughly 10,000 apparel units. And Tiruppur needs them as much they need its opportunities.

“Tiruppur is in need of migrant labourers because its own population has moved to places like Singapore, Europe, and the USA. There are hardly any Tamil workers,” Senthivel said. “So, when migrant people work here and contribute to our economy, we also want them to grow. We are happy about that.”

Most viewed

- Amid weak demand, cotton price surge adds to woes of yarn mills

- Centre willing to procure jute and cotton crop if prices fall below MSP : Goyal

- BTMA signals minimum wage structure for cotton textile sector within next two weeks

- State further subsidises power supply to textile industry till 2028

- India’s cotton yarn exports to surge by 85-90% in FY2024: ICRA

- ASEAN delegation to visit India on 17 Feb for FTA review

- Boosting trade relations with India

- Bank fraud case: Textile baron Neeraj Saluja sent to 5-day police remand

- New MSME payment rule leads to many cancelled orders

- New Rule of Payment to MSMEs Causes Uncertainty in Textile Markets

Short Message Board

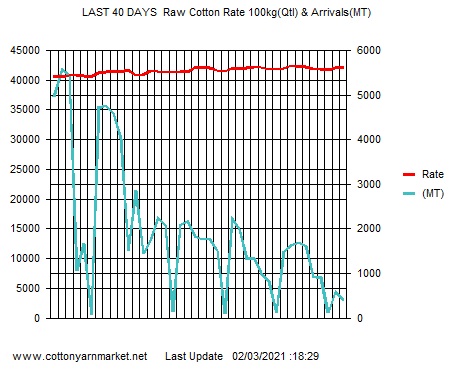

Cotton Live Reports

Visiter's Status

Visiter No. 32879060Saying...........

One man plus courage is a majority.

Tweets by cotton_yarn